Mor Temor

Arch. Mor Temor is international Architecture firm committed to designing unique buildings and one of a kind architectural concepts.

The urban block is at the same time considered the building stone of the architecture of the city and the concrete framework for living in the city; Urban Forms deals with the question of the building block, understood as an integral element of the urban tissue.

The history of the transformations of the urban block in the world is determined by structural social-economic changes that appeared as a result of the rise of industrial capitalism during the 19th century.

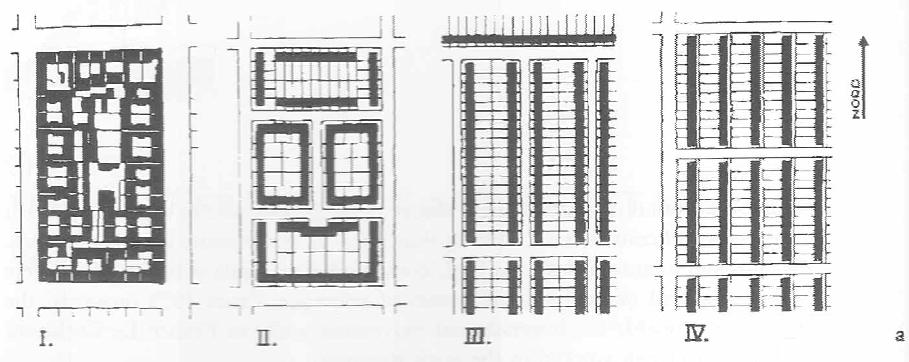

The development of the urban block can be summarized in five stages:

- The nineteenth century block, dense and compact, the interior is private and hidden. ‘Completely isolated from the street, the internal space is a place for trees and silence, allowing for individual use.’ (see Fig. 5 I).

- The hollowing of the centre and reorganization of the block’s perimeter, introducing collective gardens or small gardens connected by a collective path. ‘The opening of the block and the creation of collective gardens, accessible and visible from the street, lessened the differentiation between fronts and backs and sterilized the central space.’ (see Fig. 5 II) (François, 2005).

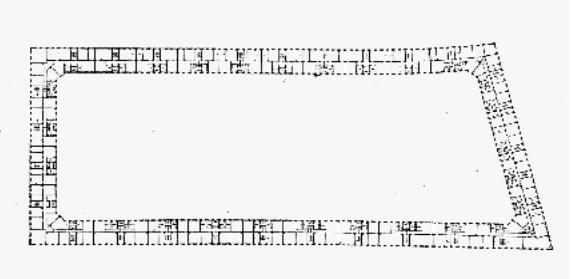

Here, the qualities of the reformed metropolitan housing block are distilled to an almost diagrammatic clarity: the building follows precisely the form of the block and thus emphasises the role of the urban street pattern. Its façade stretching over more than 200 metres radically develops the idea of uniform apartments in a democratic society through the strict repetition of a single element - the window with its remarkably simplified frame. However, behind this explicitly urban façade, a large green court provides the inhabitants with all the necessities of a pleasant place to live, namely light, air, silence, trees and meadows, offering a beautiful and safe place for recreation and play despite being in the city centre.

Due to the fact that it follows the street, the corners were preferred places for trade and this was where the corner shops were located (see Fig. 6 ) (Sonne, 2005).

Fig 6 Building follows precisely the form of the block in Copenhagen, 1922-23.

- Opening of the ends and lowering of the density, ending up a back-to back combination of two rows framing gardens. The rows become autonomous, planned to allow for maximum of sunlight, serviced by lanes perpendicular to the streets. Of the traditional block, only two principles remain: a) a clear relationship between building and its context, b) a differentiation of fronts and backs. However, the relationship with the street and connection with the city are abandoned (see Fig. 5 III).

- The suppression of the private gardens in favor of a collective lawn, combined with a weakening of the differentiation between facades. The private spaces are reduced to the inside of the dwelling and the balconies, while the less and less differentiated public space occupies the whole of the unbuilt terrain (see Fig. 5 IV).

These four steps show a process of opening the block which, seen form the perspective of the use of space, results in a mixing of fronts and backs, private, collective and public space and as such creating a ambiguous space.

Fig. 5 Layout illustrating the transformation of the urban block around 1900.

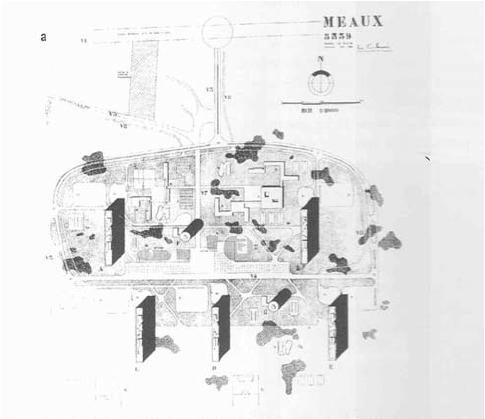

- The fifth and last phase in the development of the urban block takes place around the middle of the last century. The traditional elements of the block are cut up, rethought and rearranged in a new unit, a vertical urban block, where all traditional relationships are inverted and contradicted. The street has disappeared and turned into a ‘rue corridor’, an internal street. This spatial reorganization also involves a complete modification in the way of life of the inhabitants. In this model the old tissue has been dissolved (fig. 7+8): the traditional sequence of street/edge/courtyard/end of plot has disappeared, the contrast of sides does not exist any more an possibilities for individual appropriation and modification are nonexistent or confined to the interior of the dwelling (François, 2005).

Fig. 7 Le Corbusier, section from the Cité Radieuse plan.

Fig. 8 Le Corbusier, the Marseille Unité d’Habitation.

Arch. Mor Temor